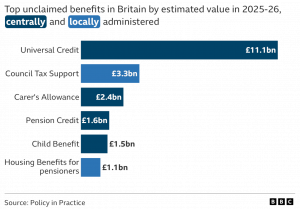

Unlocking Billions: How Community Activation Can Transform Income Security Across the UK Every year, tens of billions in welfare support allocated to households across the UK goes unclaimed. Behind these numbers are families pushed deeper into hardship, councils under mounting pressure, and communities absorbing the weight of crisis that could have been prevented. But what if the solution to this systemic gap isn’t simply better forms, new guidance, or more advertising? What if the first step in unlocking billions lies in the relationships and trust already embedded across our neighbourhoods? This was the question explored during a recent Resolve Poverty workshop, where we introduced Angels Connect – a community-activated, technology-supported model designed to close the gap between what people are entitled to and what they actually receive. The conversation highlighted both the scale of the challenge and the transformative potential of a grassroots-led response. The Scale of the Gap The numbers are staggering. In 2024/25, an estimated £11.1 billion in Universal Credit alone will remain unclaimed, with the total unclaimed benefit entitlement across the UK reaching as high as £24 billion annually. This includes £5 billion in locally administered benefits and £3.4 billion in unclaimed Council Tax Support. This isn’t theoretical money. It’s already allocated, budgeted, and intended to support the people we work with every day. The problem is that it simply isn’t reaching them. Why? Because the gap is fundamentally relational. People don’t know they’re eligible; they worry about judgement; they’re intimidated by complex systems; or they no longer trust statutory institutions because of past experiences. Crucially, many lack a trusted person who can walk with them through the first step. This is not just a financial issue – it is a justice issue. A Local Insight: North Liverpool’s Story For over twenty years, St Andrew’s Community Network (SACN) has delivered debt advice, welfare support, and community-led interventions in North Liverpool. We’ve seen lives transformed when people finally receive the support they’re entitled to: incomes stabilised, evictions prevented, wellbeing restored. But we’ve also seen a painful pattern – the people who most need advice are the least likely to access it. Often, they walk through our doors only when they’re already in crisis, when both the personal and system-level costs are far higher. This reality demanded a different approach. Introducing Angels Connect: Redesigning the First Step Angels Connect was created to shift the system upstream by equipping ordinary people in communities to notice need early, have safe guided conversations about money worries, and directly connect individuals into specialist advice via a secure digital platform. These “Money Angels” include: volunteers, church teams, pantry staff, school workers, NHS receptionists, social prescribers, housing officers, elected members, even a barber People who already hold trust- something systems can’t mandate or manufacture. Money Angels complete a short online training programme (video, quiz, resource access, safeguarding) and then use the Angels Connect app or web portal to refer people safely and directly into advice services. They don’t give advice. They simply open the door. System Infrastructure, Not Just Community Engagement Behind this sits a digital platform that connects community capacity to advice-sector capacity. It includes: a training hub, a resource library, a secure referral system, a social learning network, the ability to route referrals based on local capacity. The platform ensures cases are never lost – each person is followed through until support is received. Where It’s Already Working In under two years, the model has spread from Liverpool to other areas across the UK. The ripple effect has been profound: people who would never have accessed advice are now receiving hundreds of pounds a month in previously unclaimed support, with stabilising effects on households, mental health, and community wellbeing. The Challenge: Capacity and Systems Change But the workshop also explored an honest tension: increased demand on advice agencies requires smarter, fairer, and more transparent capacity management. Work is already underway to model provider capacity, distribute referrals equitably, integrate upstream triage, and strengthen the wider ecosystem. Angels Connect is becoming more than a community tool – it is an emerging system-wide infrastructure platform. The Return on Investment The economics speak loudly. Every £1 invested in training Money Angels yields multiple pounds in successful income claims. The result? more income entering households, reduced pressure on crisis services, lower homelessness interventions, decreased foodbank dependency, and reduced demand on GP and mental health services. Far from a “nice-to-have,” early intervention is increasingly a matter of system sustainability. A Vision for Liverpool City Region Imagine every school, pantry, GP reception, community hub, children’s centre, fire station, library, housing team, employer and local faith community functioning as a relational touchpoint – thousands of trusted connectors all feeding into a single secure pipeline. Tens of millions unlocked locally; hundreds of millions nationally. A region-wide model of upstream, relational, community-powered income maximisation. Co-Designing the Next Phase The workshop closed with an invitation: How could this work in your area? Where could it integrate? What barriers need to be understood? What would it take to build an LCR-wide pilot? These are not rhetorical questions – they are the foundation for the next phase of development, which must be shaped in partnership with people, places, and organisations across the region. Every unclaimed pound isn’t just lost income – it’s a missed moment of dignity, stability, and justice. But every Money Angel brings that moment closer. If we want to build a system that truly works for people, we need to activate the relationships that already hold communities together – and design systems that recognise, support, and amplify them. Liverpool City Region now has an opportunity to lead the country in this new, community-activated approach to income security. The door is open. The question is: How far can we push it together?

From Promise to Practice: What Budget 2025 Means for Financial Inclusion

From Promise to Practice: What Budget 2025 Means for Financial Inclusion As the new Autumn Budget lands, the government has made some bold moves, and some more subtle shifts. For Angels Connect, today’s announcements offer real reason for guarded optimism, but also amplify the urgency for robust community-level action. What gives cause for hope/ relief for many families The government has scrapped the two-child welfare limit. From spring 2026, families with more than two children on means-tested benefits will no longer be automatically capped. The switch is expected to lift around 450,000–560,000 children out of poverty, compared with previous policy. That change could mean meaningful breathing room for many low-income households – an easing of pressure on families struggling with rising costs of living. For those of our clients juggling rent, food, energy bills and uncertain incomes, that extra benefit could make the difference between coping, or crisis. At the same time, the Budget continues to recognise the need for sustained public investment. The government signals long-term capital spending and an expanded commitment to public services in the next years. For Angels Connect this reaffirms that welfare reforms and public-service investment remain high-stakes levers in reducing systemic poverty, and that policy changes still matter. But many elements of today’s Budget risk deepening financial stress The Budget also introduces a package of tax and fiscal changes raising a projected £26 billion by 2029/30. These include freezing thresholds for income tax and National Insurance, reforming pension contributions (including ending certain salary-sacrifice benefits), and raising tax on dividend, property and savings income – measures which, while targeting wealth and high earners, may still squeeze people living on variable incomes over time. Because thresholds are frozen – rather than overt rate increases – many people on low or middle incomes could effectively see their tax burden rise over time, especially if wages remain stagnant. For households already under strain, that stealth tax increase may erode any gains from welfare reforms. At the same time, new charges, such as planned mileage-based levies for electric vehicles beginning 2028, and other indirect tax rises, add layers of complexity and potential cost increases. There’s also no guarantee that increased public spending will immediately translate into scaled-up support for frontline community services – advice agencies, foodbanks, debt counselling, digital-inclusion efforts. Where resources end at high-level spending, grassroots poverty relief may go under-funded. What this means for Angels Connect: now is the moment to act The Budget underscores precisely why Angels Connect’s mission remains vital, perhaps more than ever. Policy shifts can create openings. But for those openings to be more than just rhetoric, we need robust, community-level delivery. As more families gain access to benefits thanks to the lifted cap, demand for debt and welfare advice – the core of Angels Connect – will likely rise. Our network and referral infrastructure must be ready to absorb and respond to increased need. The stealthier tax changes risk pushing more people toward precarious finances, meaning more people may need support, whether with budgeting, debt, benefits access or simply stabilising their household. Angels Connect must be positioned to respond swiftly. This Budget could represent a pivotal moment: a chance to move from policy promise to real-world financial resilience. But only if the civil-society sector, funders and local authorities commit to ensuring that increased public funds are matched by strengthened community-level infrastructure. A call to solidarity from policymakers, funders, and community partners If this Budget’s welfare reforms are to deliver real justice and inclusion, then: Policymakers must follow through – ensuring that additional welfare spending and public investment are not swallowed by central bureaucracy, but channelled toward local infrastructure: foodbanks, debt advice, housing support, and holistic inclusion programmes. Funders and donors must recognise the shift – as increased benefit eligibility could generate higher demand for support services, we need investment not only in emergency response (food, crisis support) but in sustainable advice, prevention and empowerment. Community organisations must collaborate – and scale up intelligently. Angels Connect’s referral-based, triaged model is exactly what’s needed to translate welfare reform into real human dignity. We must strengthen our networks, deepen partnerships, and prepare now. We must frame today’s Budget not as an end – but a milestone. Welfare changes are important. But they only succeed if matched with strong delivery on the ground, financial literacy, affordable credit access, and community support systems. That remains our mission. In short: the budget brings hope, especially for larger families finally spared a punitive welfare cap. But at the same time, its broader fiscal strategy leans heavily on tax rises, spending freezes and indirect levies – moves that risk widening inequality if not properly managed. For Angels Connect (and everyone committed to financial inclusion) this is a moment to double down. Not just to celebrate the wins, but to build the systems that turn promise into sustainable public-good – one family, one household, one community at a time.

From Promise to Practice: A Strong Step in the UK’s Financial Inclusion Journey

From Promise to Practice: A Strong Step in the UK’s Financial Inclusion Journey Much like the way that open, community-driven approaches can tackle multiple deprivation, we need to view the recently published Financial Inclusion Strategy (FIS) from HM Treasury not simply as a policy document, but as a platform from which community-based action and systemic reform must flow. The Strategy offers welcome commitments, but the social sector – particularly grassroots organisations working with deeply excluded communities – must press for rigour, resourcing and co-creation if we are to move from rhetoric to real change. At its core, the FIS defines financial inclusion as: “everyone can access the financial products and services they need, manage their money with confidence, and plan for the future.” The document identifies six key domains: Digital inclusion and access to banking Savings and resilience Insurance and financial protection Access to affordable credit Tackling problem debt Financial education and capability There are also three cross-cutting themes: mental health, accessibility, and economic abuse – recognition that financial exclusion is rarely a singular cause, but layered. In practical terms, the Strategy commits to: A new £30 m fund to support credit union transformation across England A pilot for small-sum lending via Fair4All Finance Making financial education compulsory in primary schools in England Enabling workplace savings / payroll savings schemes through regulatory clarity A pilot with major banks to allow people without a fixed address to open a bank account From a community-led, “bottom-up” lens, the Strategy is important for several reasons: 1. Acknowledging the scale of exclusion The fact that the Strategy explicitly recognises that millions of people are financially excluded or fragile – whether through lack of savings, credit problems, or access barriers – opens a door into systemic thinking. Tackling this exclusion could unlock billions in economic and social value each year. 2. Linking financial inclusion to broader social agendas Financial exclusion doesn’t exist in isolation. By embedding themes of economic abuse, mental health and accessibility, the Strategy aligns with agendas on deprivation, homelessness, and inequality. This means those working in social impact should see it as an invitation to integrate money and finance into broader community models, rather than treat them in silo. 3. Opening up multiple entry-points for change The Strategy doesn’t rely solely on “new products” but emphasises education, access, capability, employer engagement, regulatory clarity, and community finance infrastructure. That breadth creates opportunities for local ecosystem actors who may already be working in one or more of these domains. 4. The language of partnership and lived experience The Strategy was shaped with input from a Financial Inclusion Committee comprised of consumer and industry representatives, and emphasises that lived experience matters. That signals fertile ground for civil society organisations to engage, influence and co-design. While there is much to applaud, the real question will be: will this translate into deep, sustained, structural change? On that front, there are some caution lights: 1. Ambition versus structural drivers Some sector responses argue the Strategy consolidates rather than transforms. Access and education are necessary but insufficient if underlying income insecurity, housing instability, digital exclusion, and predatory credit remain unchallenged. 2. Metrics, accountability and local implementation Progress is to be reviewed in two years using outcomes-based metrics. But for many of the people we serve, the urgency is now. Interim milestones, transparent local dashboards, and rigorous community-level evaluation are essential. 3. Scaling community finance & local infrastructure The £30 m credit union transformation fund is welcome, but given the scale of need, it must be matched by investment in digital infrastructure, data sharing, and referral networks that allow local actors to collaborate effectively. 4. Employer-based savings and reach Payroll savings are valuable, but primarily benefit those in stable employment. A strategy for those in precarious work, self-employment, or benefit dependency remains underdeveloped. 5. Digital inclusion and the “last mile” Access to banking, digital ID, and inclusive design are embedded in the Strategy, but delivery for underserved locales (rural, marginalised, non-English speakers, disabled users) will determine its real success. If the Financial Inclusion Strategy provides the framework, then models like Angels Connect show what that framework looks like in practice. Born out of the advice and community support sector in Liverpool, Angels Connect is building the connective tissue between financial inclusion, advice access, and community data – creating an open referral and triage network that helps people navigate complex systems of debt, welfare, and digital exclusion. Rather than treating each problem in isolation, Angels Connect links local advice agencies, foodbanks, and community partners into a shared digital infrastructure that ensures no one falls through the cracks. Every referral, every data point, and every insight contributes to a bigger picture of local need – the kind of insight that policymakers now call for in the national strategy. In effect, it demonstrates what “financial inclusion as social infrastructure” looks like: Human-centred access – meeting people where they are, not where the system expects them to be. Data with democracy – empowering communities to own their information and use it to shape fairer systems. Connected delivery – reducing duplication, strengthening partnerships, and ensuring frontline agencies have the information they need to act quickly and effectively. If the Strategy sets the ambition nationally, platforms like Angels Connect make that ambition actionable locally. They show that inclusion isn’t achieved by new products alone, but by joining the dots between the institutions that serve people and the people they’re meant to serve. Given the policy platform now exists, this is our moment to mobilise. Here are five key actions for the community sector to own: Use the Strategy as a tool for local systems changeTranslate national commitments into local ecosystems: housing advice, employment support, community banking hubs, debt advice clinics. Collaborate – co-design, not deliver in isolationStep up as co-designers with banks, fintechs, employers and local authorities, bringing the voices of lived experience to the table. Make data democraticCapture and share local data on who is excluded, why, and what interventions work. Demand transparency from national

Rethinking Civil Society: From Charity as Usual to a Shift Beyond the Status Quo

The recent release of the English Indices of Deprivation 2025 (IoD 2025) offers a sobering reminder: despite decades of policy, philanthropic and voluntary-sector effort, many parts of the UK remain locked into persistent, multi-domain disadvantage. With this data in hand, the question must shift from “What more can we do?” to “Are we doing the right thing, and is our model capable of what is required?” In this light, the framework advanced by Shift Beyond conversations, emphasising a disruption of current norms in civil society, peer-led agency, and a re-imagining of mission and structure becomes critically relevant. The IMD 2025 ranks neighbourhood-level areas (LSOAs) by their levels of multiple deprivation across the seven domains: income, employment, education/skills, health/disability, crime, housing/services access, living environment. Key points: Many LSOAs falling into the most-deprived deciles are highly disadvantaged across multiple domains rather than just one. Change is slow: some areas remain in the bottom decile across multiple releases of the Index (so-called “persistent deprivation”). The challenge is not simply income poverty, but a clustered set of disadvantages which often reinforce one another (e.g., poor employment + low skills + ill-health + insecure housing) and thereby lock places into disadvantage. If we reflect on the objectives of the anti-poverty sector over recent decades – reducing disadvantage, increasing opportunity, building resilient communities – the data suggests that, in many places, those ambitions have not been met as fully as hoped. The structure of disadvantage remains entrenched. We must ask: if so many parts of the sector are committed, funded, and active, why is persistent multi-domain deprivation still so visible? Some of the reasons can be traced to the architecture of civil society and the design of “impact-centres” as they currently function. Fragmentation and siloed missionsMany charities, social-enterprises and community organisations specialise in one domain: food security, debt advice, skills training, housing support, community health. Yet the IMD shows that individuals in high-deprivation neighbourhoods often face combined challenges across domains. As a result, a collection of siloed services may struggle to tackle the compounding effects of multi-domain disadvantage. Service-delivery rather than system redesignMuch of the sector focuses on service provision: delivering to those in need, responding to crisis. This is vital, yet if the core structural challenge is interwoven disadvantage, then reacting to it may have limited transformative effect. The sector may be better geared to mitigate rather than eradicate. The anti-poverty ambition requires redesign of systems, not only delivery of programmes. Top-down models, limited community agencyMany organisations are structured in hierarchical ways, with leadership and funding decisions largely above community actors. While community organisations exist, the broader ecosystem still tends to treat “beneficiaries” as recipients rather than co-creators of change. Shift Beyond emphasises shifting power to community agency, yet many impact-centres retain traditional power dynamics. Measuring what is easy, not what matters mostWith multiple deprivation showing entrenched disadvantage, the focus of many charities on outputs (people served, sessions delivered, meals supplied) may not align with the harder-to-measure but deeply important outcomes (community resilience, inter-generational mobility, dismantled systems of disadvantage). The status-quo model is not always calibrated for the long-haul structural change needed. Scaling the wrong thingScaling has become a mantra: more reach, more sites, more beneficiaries. But if the underlying model is flawed (fragmented, service-led, siloed) then scaling doesn’t necessarily translate into deeper structural impact, it may simply reproduce the same patterns in more places. The persistence seen in the IMD data suggests that more of the same will not suffice. The language of Shift Beyond invites us to go further: to imagine civil society not simply as “impact-centre doing good” but as a transformed ecosystem of community-led action, networked infrastructure, and systemic redesign. Key elements include: Peer-led agency: shifting from ‘service users’ to ‘co-creators’. Communities most affected by disadvantage are not passive recipients but must be given voice, resource and structural role in designing responses. Open, networked platforms: rather than discrete programmes, a network architecture that connects people, referrals, support, skills, peer-networks and systems change through digital and local infrastructure. Multi-domain alignment: the model must reflect the cross-domain nature of deprivation. That means designing interventions that integrate employment, housing, health, skills and community agency rather than addressing them individually. Distributed power, transparency and shared leadership: the sector must embrace new governance, open access, decentralised decision-making, aligned with the ethos of democracy and equity. Metrics of deeper change: shifting from throughput to transformation: measuring community resilience, sustained mobility, changes in structural disadvantage. Adaptive funding and partnerships: funders and charities alike need to embrace risk, innovation and learning-rich models, rather than rigid programmes whose logic ends at “deliver and report”. In short: the civil society model needs to transition from a “helping” paradigm to a “co-creating” paradigm. The data demands it: The IoD 2025 shows not only the scale but the persistence of disadvantage. When many areas remain locked in disadvantage across time, the case for incremental service-improvement is weak, what is required is structural redesign. Policy momentum: Governments are increasingly acknowledging the limits of siloed policy and are looking for joined-up, community-driven models. The sector must align with this shift. Technology & network infrastructure: Digital platforms, referral systems, community data-tools and distributed networks now offer possibilities that earlier models lacked, opening the door to redesigned civil society architecture. Funding pressure: With public finances constrained and demand rising (cost-of-living, health, inequality), charities and social enterprises cannot assume old models will be sufficient or sustainable. For leaders in the sector, the narrative of “scale what works” must be replaced by “design what is needed”. Questions to ask: Are we working in silos? How might our work better integrate with other domains of disadvantage? Do the people we serve have structural voice, decision-making power and agency within our organisation or network? Are we tracking the outcomes that matter for structural change (mobility, community leadership, systems shift) or only the outputs we can easily measure? Are we building platforms and networks rather than isolated programmes? Are our funding and governance models aligned with distributed power,

From Data to Democracy: Tackling Multiple Deprivation through Open, Community-Driven Models

From Data to Democracy: Tackling Multiple Deprivation through Open, Community-Driven Models The publication of the latest Index of Multiple Deprivation 2025 (IMD 2025) paints a stark picture of the scale and persistence of deprivation in England, and by extension the UK. But amid the sobering data lies a clear mandate: the only path to genuine change is via democratised, open-to-all initiatives that empower communities, not simply treat symptoms. In this light, initiatives such as Angels Connect offer a vital model – one that moves beyond charity to community agency, connecting individuals to advice, resources and networks in ways that align with the systemic challenge laid bare by the data. The IMD 2025 has been published by the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government and ranks 33,755 Lower-layer Super Output Areas (LSOAs) in England by levels of multiple deprivation. The seven domains captured – income, employment, education/skills & training, health & disability, crime, barriers to housing & services, and living environment show how deprivation is not simply an income problem but a cluster of intersecting risks. Some of the key findings: Among the most deprived 10% of neighbourhoods (3,375 LSOAs), 99.1% are in the most deprived decile on at least 2 domains and 67.2% on four or more domains. At local authority level, some areas show very high concentrations: for example, Middlesbrough has 50 % of its LSOAs among the most deprived 10% nationally. More than half of the LSOAs that rank among the most deprived 1% nationally in 2025 have been in that group in every published version of the IMD since 2004, signalling deep, persistent deprivation. Geographical patterns remain: the Midlands, North, coastal and post-industrial towns dominate the bottom rankings. But crucially the data also shows that deprivation is not confined to remote or rural areas, it is strongly present in urban neighbourhoods locked into multi-domain disadvantage. In sum, the data confirms what many frontline agencies observe: deprivation is structural, multi-dimensional and deeply rooted. It cannot be addressed solely through isolated interventions (e.g., only food support or only housing subsidies). The problem requires an integrated approach – one that unlocks agency, addresses root causes (employment, skills, rights), and builds resilient social systems. Given the data, policy must move beyond the “targeted safety net” model to embrace a more open, inclusive and system-wide response. Here are three imperatives: From targeted to universal access in advice and support. Areas in the poorest deciles suffer multiple burdens simultaneously – joblessness, poor health, low educational attainment, insecure housing. So limiting services only to those deemed “most in need” runs the risk of missing many who fall just outside thresholds but are still exposed to multi-domain disadvantage. Universal access to high-quality advice (on debt, welfare, employment, housing) should be considered a public good. This reflects a shift in thinking: from reactive to preventive, from crisis-management to empowerment. Local networks, digital referral and community agencyThe geography of deprivation shows persistent neighbourhood disadvantage. Policy therefore must invest in local networks that are embedded in community life, digital platforms that facilitate referral and triage of need, and training that enables neighbourhood actors (volunteers, community workers) to act as connectors. This is an inclusive model: open to all, not just those already in the system. Data-driven, but democratised decision-makingThe IMD 2025 data is vital, but the translation from insight to action must involve local voices. Data should underpin but not dictate strategy. Residents of deprived areas must have a voice in shaping how services are delivered, and how open-access platforms are configured. Moreover, the domains show that interventions must span welfare, housing, employment, health – so policy must join up across silos. Angels Connect is an exemplar of the kind of democratised, inclusive initiative policy should encourage. Rooted in the community, digital-enabled, and open to all who are navigating life-challenges, it offers a fresh blueprint, one aligned with the structural nature of deprivation the IMD 2025 reveals. Open access, not gate-kept: Rather than being confined to narrowly defined benefit recipients, Angels Connect’s model allows anyone to engage with training, advice, digital referral and community networks. This aligns with the universal-access imperative above. Referral infrastructure meets lived experience: Recognising that people living in deprived areas interact with multiple systems (housing, benefits, debt), Angels Connect offers a referral network and triage model connecting people to life-changing advice. This resonates with the IMD’s multi-domain nature of deprivation. Community capacity building & empowerment: The model does not only deliver services, it builds capability in communities, enabling volunteers and local actors to participate. This helps shift neighbourhoods from being passive recipients to active agents of change, which is critical in places where multiple domains of disadvantage are entangled and long-standing. Policy influence embedded: Angels Connect also advocates for systemic change (income security and welfare reform), not simply service delivery – which aligns with the data showing that structural disadvantage underpins the most deprived areas and that piecemeal responses will not suffice. — The IMD 2025 makes plain the challenge: entrenched deprivation, multi-domain disadvantage, and geographic concentration. Tackling this requires a paradigm shift in how we design and fund interventions: Investment in place-based digital referral networks: Government should support the scaling of open-access platforms (such as Angels Connect) across local authority areas. These networks must be interoperable, data-informed, and locally embedded. Incentivise community-led frameworks: Funding programmes should reward initiatives that enable local actors to partner in delivery, co-design solutions and build local capacity, not just contract large providers. Embed universal advice provision: Universal welfare, debt and employment advice should be considered a core public infrastructure. Just as highways or health systems are funded universally, so too should access to advice that helps people navigate complex systems and avoid spirals of multiple disadvantage. Align metrics with multidimensional outcomes: Rather than measuring in narrow silos (e.g., number of food parcels delivered), policy must measure across domains – improvements in employment, housing stability, debt resolution, mental health recovery, and community resilience. Data such as IMD 2025 should be used to map progress neighbourhood by neighbourhood.

Shift Beyond | In conversation with Nic Whyley, The University of Salford

Shift Beyond | In Conversation with Nic Whyley & Rich Jones What if the very thing we’ve been taught to chase – growth- is actually part of the problem? That’s the provocation behind Shift Beyond Conversations, a podcast series exploring how we might tackle poverty, inequality, and injustice without falling into the trap of empire-building. Hosted by Rich Jones, CEO of St Andrew’s Community Network in North Liverpool and the social enterprise Angels Connect, each episode challenges conventional thinking about the charity and impact sector; inviting leaders, funders, and thinkers to ask hard questions about what real change looks like. In this episode of Shift Beyond Conversations, host Rich Jones sits down with Nic Whyley, Senior Philanthropy Manager at the University of Salford, to explore how higher education can rediscover its purpose in a post-growth world – one where institutions are being called to listen, to partner, and to root themselves once again in the communities that built them. At a time when universities across the UK face what Nic calls an “existential moment,” this conversation asks a simple but searching question: what if growth isn’t the goal – but grounding is? Nic reminds us that the University of Salford’s story began not as an ivory tower, but as a Royal Technical Institute, founded in 1896 to serve local industry during the Industrial Revolution. It was built for the people, by the people, a university of place and purpose. But in a landscape dominated by global rankings and international recruitment, universities risk forgetting the power of their proximity. “There’s a disconnect,” Nic explains, “between what happens inside the walls of a university and what happens outside.” Her call is to rebuild those bridges – to see universities as civic ecosystems capable of tackling inequality, improving life expectancy, and driving local regeneration alongside councils, charities, and businesses. Nic leads the University of Salford’s philanthropy and stewardship team, a role that goes far beyond fundraising. She describes philanthropy not as transaction, but transformation, about co-design, not donation. As she puts it, growth in philanthropy “isn’t the problem, unless it becomes disconnected from purpose.” The real task is ensuring funding reaches the right people, reflects the identity of place, and creates long-term system change rather than short-term success stories. That philosophy comes to life in the University of Salford’s partnership with Tutor Trust, a Manchester-based charity that trains university students to mentor pupils in local schools. The results have been transformative: a 10% rise in English and Maths attainment, and new confidence for both students and schoolchildren. It’s philanthropy as relationship, not reach – a living example of the shift from giving to growing together. When asked how universities can avoid becoming extractive in their community partnerships, Nic is clear: “Relationships become extractive when they’re not two-way.” For her, genuine partnership means dialogue, humility, and co-created solutions – research that listens before it leads, funding that invites participation, and institutions that see themselves as in community, not above it. This approach redefines success. It moves from measuring outputs to measuring equity, from growth in size to growth in solidarity. Nic shares one striking statistic: around 80% of Salford’s students come from widening participation backgrounds. Access isn’t the challenge, equity is. The university is working to level the playing field between students who enter with A-Levels and those with BTECs, redesigning its curriculum to reflect diverse educational journeys. “It’s not about growing bigger,” she says, “it’s about closing the gaps.” From early years outreach to curriculum reform, the university’s focus is shifting – from prestige to participation, from expansion to inclusion. As the conversation closes, Nic offers a simple challenge to leaders everywhere: “Keep coming back to purpose and mission. Listen, collaborate, think, and do. And keep checking ourselves – are we still giving voice to those who most need to be heard?” Rich reflects that generosity isn’t just financial, it’s structural. It’s about who holds power, who gets to define success, and whether the systems we build truly listen. Building solutions without building empires takes courage, the courage to fund differently, partner differently, and lead differently. — The Shift Beyond podcast is supported by Angels Connect, a social enterprise born from St Andrew’s Community Network in North Liverpool. Angels Connect is more than a sponsor, it’s a live case study of the Shift Beyond philosophy in action. Developed to redesign access to debt and welfare advice, it puts the power to connect people to help directly in the hands of communities – teachers, faith leaders, health workers, neighbours – enabling anyone, anywhere, anytime to make a referral within minutes. Rather than scaling traditional charity models, Angels Connect reimagines how support systems can work: lighter, faster, more relational, and more human. Rich Jones, CEO St Andrew’s Community Network/ Angels Connect Nic Whley, Senior Philanthropy Manager The University of Salford

Shift Beyond Podcast | Nic Whyley & Rich Jones

What if growth isn’t the goal, but grounding is? In this episode of Shift Beyond Conversations, host Rich Jones opens up an honest and hopeful dialogue with Nic Whyley, Senior Philanthropy Manager at the University of Salford, about what it means to rediscover purpose in a world where institutions often confuse size with significance. The Shift Beyond series explores a radical reframe: what if success isn’t measured in how big our organisations become, but in how deeply they stay rooted in the communities they serve? Across each episode, leaders, thinkers, and practitioners explore how we can build solutions without building empires – how we design systems that listen before they lead, share power rather than hoard it, and create impact that lasts longer than any single project or institution. This conversation takes us inside one of the UK’s most civic-minded universities, a place where the walls between academia and community are deliberately being dismantled. Nic shares how the University of Salford is reconnecting with its original mission as a technical institute for working people, and what that history can teach us about the future of higher education. Together, Rich and Nic unpack the biggest questions facing universities, funders, and civic institutions today: What happens when “growth” becomes the default measure of success? How can philanthropy move from transaction to transformation – from donations to shared design? What does it look like for universities to act not as empires, but as neighbours co-creating with the communities around them? And how do we design learning systems that don’t just widen participation, but close the gap between opportunity and equity? Throughout the conversation, Nic reflects on how the University of Salford’s partnerships – like its work with Tutor Trust, where students mentor local schoolchildren – are helping redefine what it means to study, to serve, and to succeed. It’s a model of education that grows people, not just institutions. The episode invites listeners to reimagine what growth could mean when it’s grounded in purpose. It’s a conversation about humility, partnership, and the quiet courage it takes to build systems that share power, not prestige. It reminds us that impact isn’t about getting bigger, it’s about getting closer. Hosted by Rich Jones, CEO of St Andrew’s Community Network and Angels Connect. Produced in partnership with Shift Beyond and Angels Connect – reimagining systems for dignity, justice, and change. Nic Whyley, Senior Philanthropy Manager The University of Salford Rich Jones, CEO St Andrew’s Community Network/ Angels Connect

Public Interest Plumbing: Building the Hidden Infrastructure of Change

We talk a lot about values in the social sector – purpose, justice, dignity, equality. These words shape our movements and inspire our missions. But between the ideals and the impact lies something less glamorous, and just as essential: the plumbing. The way water runs through a city, the way a current passes unseen through walls – that’s how public interest flows, too. It needs pipes. It needs systems. It needs maintenance. And if we want our movements for justice and community transformation to last, we need to pay as much attention to the plumbing as we do to the poetry. That’s the heart of Public Interest Plumbing; a phrase that captures the often-hidden work that makes social change possible. It’s the systems that connect people to resources, ideas to action, and policies to lived outcomes. It’s the craft of designing, maintaining, and repairing the unseen networks that allow dignity to circulate. Beyond Ideology, Toward Methodology Over the past few years, many of us have begun to “shift beyond” the old ways of doing good. We’ve realised that compassion alone doesn’t create justice, and that growth isn’t the same as progress. The Shift Beyond conversation has helped name that truth – but what happens next? Public Interest Plumbing is one possible answer. It’s the bridge between belief and behaviour, between ideology and methodology. It reminds us that what holds communities together isn’t just shared vision, but shared systems. Without functioning plumbing, even the best intentions leak. Without maintenance, even the boldest reforms clog up. It’s an approach that says: before we build new programmes or campaigns, let’s map the flow. Let’s ask how ideas travel through people, processes, and institutions. Let’s notice where they stall, where they overflow, and where the pressure builds. The Social Science of Plumbing The idea has deeper roots than it might seem. In her essay The Economist as Plumber, Nobel laureate Esther Duflo urged policymakers to focus on the practicalities of implementation – the fittings, the valves, the ways systems really behave under pressure. Philosopher Mary Midgley once called her discipline “philosophical plumbing,” because every big idea sits on a hidden network of assumptions that needs repair. Sociologists, too, have long studied the “invisible mechanics” of social life: how institutions maintain trust, how networks carry cooperation, and how bureaucracies shape access to power. Anthropologists talk about infrastructural intimacy, the ways systems quietly affect daily life. Public Interest Plumbing draws on all of this. It invites us to study – and then redesign – the civic infrastructure that turns public interest into public good. Plumbing in Practice You can see it in action in places where systems quietly work better than they used to – not because someone launched a new campaign, but because someone fixed the pipes. Take Angels Connect for example. On the surface, it’s a digital referral tool helping people in financial hardship connect with local advice and support. But underneath, it’s a re-engineering project: training “Money Angels” as local connectors, creating data pathways between community groups and advisers, and ensuring people aren’t lost between services. It’s public interest plumbing, designed for flow, not just for show. Or consider the Trussell Trust’s move to digital referrals. For years, paper vouchers were a quiet source of friction and stigma. The switch to a national, data-secure system has transformed the experience for both volunteers and guests. The plumbing improved, and with it, dignity flowed more freely. Public interest plumbing isn’t just about the voluntary sector. It’s at work in the Government Digital Service (GDS) and Public Digital, who help build the pipes of modern democracy: open data standards, interoperable systems, and human-centred design that keeps public value moving. Or in community energy cooperatives across Wales and Scotland, where citizens share ownership of the energy that powers their homes – a literal and metaphorical rewiring of the system. The Craft of Keeping Systems Flowing Public Interest Plumbing isn’t glamorous. It doesn’t produce headlines or hashtags. It’s the maintenance work; the inspection, the quiet fixes, the patient iteration. It’s about understanding how things actually work beneath the surface: how referrals are handled, how feedback loops close, how accountability travels through an organisation. It’s about paying attention to leaks, the small places where people fall through cracks or data disappears, and knowing how to fix them. Most importantly, it’s relational. Systems only flow when trust flows. The volunteers, advisers, and connectors who make those systems work are as vital as any piece of technology. The plumbing isn’t just digital; it’s human. A Methodology for the Shift Beyond If Beyond Altruism challenges us to rethink how we define success – not by growth, but by freedom – Public Interest Plumbing gives us a way to make that freedom practical. It’s a reminder that justice doesn’t just depend on who holds power, but on how power flows. It’s an invitation to see every organisation, every network, every service as a system of pipes, and to take responsibility for how well those pipes serve the people they’re meant to reach. Because when we get the plumbing right, everything else works better. And when we don’t, even the most inspiring vision can’t hold water. Closing Thought We often celebrate the architects of social change – the visionaries, the campaigners, the funders. But the real test of a movement lies with its plumbers: the people who build the systems that make good intentions durable. Public Interest Plumbing is about honouring that work – and about joining it. Because the future of civil society won’t just be written in manifestos. It will be built, pipe by pipe, by those who keep the flow of dignity moving. Rich Jones, CEO St Andrew’s Community Network/ Angels Connect

What if the crisis we face isn’t just one of poverty or policy, but of trust?

What if the crisis we face isn’t just one of poverty or policy, but of trust? In this episode of Shift Beyond Conversations, host Rich Jones asks what it would mean to rebuild connection in a time of fracture, when people feel abandoned by systems that were meant to help. Drawing inspiration from Andy Burnham’s recent call for a “culture of encounter,” Rich explores how trust, dignity, and local agency can be restored in communities hollowed out by distant decision-making and soulless bureaucracy. The Shift Beyond series continues to explore a radical question: what if real change doesn’t come from growing institutions, but from deepening relationships? Across each conversation, thinkers and practitioners imagine how we can build systems with people, not for them – replacing efficiency with empathy, and power-hoarding with power-sharing. In this reflective solo episode, Rich unpacks three movements: 1⃣ Naming the fracture: understanding why trust is thin and connection brittle. 2⃣ Reimagining the local: shifting from systems at people to systems with people. 3⃣ Practising the shift: small, practical ways we can build a culture of encounter in our everyday lives and leadership. Along the way, Rich shares how Angels Connect, a social enterprise born from St Andrew’s Community Network, embodies this philosophy in action – redesigning access to debt and welfare advice through trusted community spaces, so that help feels human again. This episode is both a diagnosis and an invitation: to move from suspicion to solidarity, from empire-building to encounter. It’s a reminder that trust isn’t a by-product of better systems, it is the system. Hosted by Rich Jones, CEO of St Andrew’s Community Network and Angels Connect. Produced in partnership with Shift Beyond and Angels Connect – reimagining systems for dignity, justice, and change.

Empowering Stability: Why Angels Connect Is More Than Aid

Unlocking Billions: Why Angels Connect Could Change the Game Billions of pounds meant for the UK’s most vulnerable are forecast to go unclaimed this year. According to Policy in Practice data shared by the BBC, an estimated £11.1 billion of Universal Credit alone will go unclaimed in 2025-26, alongside billions more in Council Tax Support, Carer’s Allowance, Pension Credit, and Child Benefit. This isn’t a funding shortfall. The money is there, it’s just not reaching the people who need it most. The BBC article highlights a truth those of us working in communities see every day: the problem isn’t always a lack of provision, it’s a lack of connection. People don’t claim what they’re entitled to because: They don’t know they’re eligible. The process feels intimidating, confusing, or too time-consuming. They’ve had poor experiences with “the system” and no longer trust it. There’s no one to walk with them through the process. This isn’t just a bureaucratic quirk, it’s a justice issue. Billions of pounds not claimed means billions not flowing into households, neighbourhoods, and local economies where they could stabilise lives. This is where Angel Connect fits in. Angels Connect directly tackles this access gap. Community-level confidence: Our training modules give ordinary volunteers and staff the ability to spot unmet need early and start a safe, informed conversation. Trusted relationships: People are far more likely to act on advice when it comes from someone they already know – a school worker, a faith leader, a community volunteer. Secure pathways: Digital referral tools mean cases don’t get lost. People are followed through until they receive the support they’re entitled to. In short, Angels Connect turns unclaimed entitlements into real help, real money, and real hope for households. Leaving £11.1bn in Universal Credit unclaimed isn’t just a tragedy — it’s a missed opportunity. Unclaimed benefits lead to: Worse health outcomes, driving up NHS costs. Housing insecurity, leading to expensive crisis interventions. Higher food bank demand, stretching voluntary sector capacity. Angels Connect acts upstream, preventing those downstream crises by making sure people get what’s already theirs. If every £1 spent on Angels Connect training and referrals results in multiple pounds in benefits successfully claimed, the return on investment is enormous, not just for households but for public services and local economies. Funders and partners have a chance to turn the tide. Supporting Angels Connect isn’t simply supporting charity. It’s building a community infrastructure that pays back many times over. As the BBC article makes clear, the money is there, we just need to unlock it. Local authorities: Embed Angels Connect into libraries, schools, and community hubs. Funders: See this as an investment in poverty prevention, not a sticking-plaster cost. Community groups: Train your volunteers and staff; become trusted guides for those who don’t know where to turn. Because every pound claimed is a step toward dignity, stability, and justice.